Today I’m going to answer a question that I received by mail from Listener John Grant about what in a scene I choose to meter from for optimum exposure. John asks, “Would you discuss exposure and how to get the best possible, from what to look for in the scene and where to place the meter of your camera. For example do you choose the highlights to meter from or something else?” Thanks for the great question John. I’ll go on to explain about what I look for in a scene, the metering modes I use, and why, and we’ll also get pretty heavily into looking at some histograms. Much of what I say about histograms or at least the checking of them in the field will not be relevant to film users, but the histogram is a key part of my shooting these days, and I wouldn’t be able to talk about metering and the confirmation of results, without getting into some details. So if you are a film user, please bear with us on this, but if you are scanning your film and post processing in a tool like Lightroom or Photoshop, the histogram discussion will still be relevant. Anyway, let’s see if I can explain my methods in a way that will help John and all of you in some way.

Well, it turns out that John’s question is formatted in such a way that it really does help me to answer, because it’s very important to think about the scene you’re about to photograph before you consider what to meter on, and how to use that information. The first thing I do when getting ready to shoot a scene is look, and think about what is in the scene. Obviously, I’m doing this already from a compositional perspective, but I also start taking note of the light in the scene at the same time. If the scene is relatively evenly lit, without too many highlights, whites or other bright colours, or too many dark shadows or large black or dark coloured objects, then it’s all really quite easy. I can just throw my camera into Aperture Priority mode and leave the exposure compensation at zero, and start shooting. I will though still take a look at the histogram after the first shot or so and make sure that I am not over exposing anything. I find that with digital, unless the main subject I’m trying to depict is in deep shadow, I rarely worry too much about the shadows. There will be times when we will need to make sure there is some detail left in the shadows, but far more often, it will be the highlights we have to take care of.

I’ve said many times that I believe we should always try to get exposure as close as possible in the field, and I really don’t like the trend towards sloppy shooting and then fixing in post processing. Of course, everyone is entitled to their own way of shooting, but I personally want to give my images a chance to be as best as they can. If you shoot a great photo, then the first thing you have to do is push the RAW or JPEG file by two stops before you can even use the image, you’re not giving it much of a chance in life. Anyway, whether we’re talking highlights or shadows the one thing to always bear in mind is if depicting your subject in the way you’d like depends on having detail in either the highlights or the shadows you have to get the exposure right or close to it. Once you hit total black or pure white, there is no detail to draw out of that area of your shot, so no amount of post processing will bring it back, no matter what tools or techniques you use.

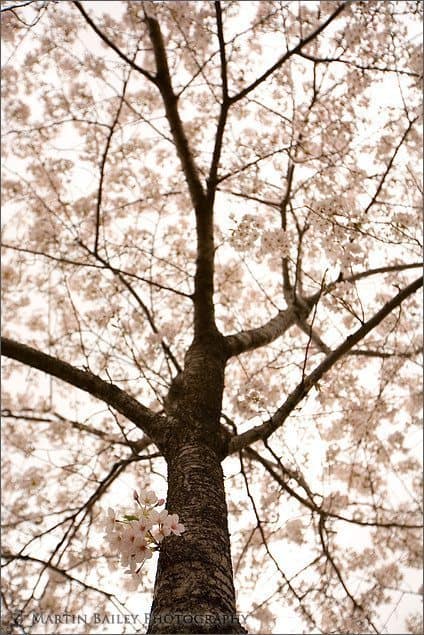

So let’s talk a little about the histogram, our main tool for checking to see if we’re on the right track. You may have heard that a histogram should be a nice hill or mountain shape, with a peak or a number of peaks around the middle and the slopes of the hill tapering off to the left and right sides. This is a good description of the histogram for an averagely lit, or I suppose I should say a properly exposed scene without too much dynamic range. That is without too much highlight or shadow. Not a perfect example, but let’s take a look at a shot from last Saturday, as it’s still fresh in my mind. I’m not going to go into details about the shot itself, but rather concentrating on the histogram. If you are going to view the image by punching the number into my Web site’s top page or podcast page, it is number 1366. Now, if you are listening to the Enhanced version of this Podcast in iTunes or on an iPod that supports Enhanced Podcasts, that have the M4A extension, you’ll be able to see the image right now and next we’ll look at the histogram. If you are following in another tool though, to continue, you’re going to have to go to the Podcasts forum at martinbaileyphotography.com and look at some images I’ll add as a companion post for this podcast. In fact, for the forum post, I’ll put an image of the whole of my Lightroom window, so you can see the image under discussion, and its histogram. I’ll also put a link to that in the show-notes to save searching around for it.

Anyway, you’ll see in the first image some nice pretty pink cherry blossom. I’m going to get into how I shoot and some metering mode stuff soon too, but for now, just note that I was using my camera in Manual Mode, as opposed to Aperture Priority and the metering mode was Centre Weighted. You can see that there are lots of bright areas in the shot, and there is a darker background than the flowers. This is why I switched to manual mode. Next though, I’m going to display the histogram for this shot in the Enhanced Podcast. I’ll throw just the histogram file into the MP3 version as well, in case you are flicking through the images yourself in iTunes, but otherwise, please just go to the forum and view the histogram in the snapshot of Lightroom. You’ll be able to see that this first histogram is a pretty typical one. You’ll see that we have some nice rounded hills on the right hand side, which is going to be those nice pink flowers, and as we look across to just left-of-centre, we can see the multiple peaks which represent the slightly darker areas of the background. We can tell from this histogram that no areas are over or under exposed. We know this, because the histogram slopes off nicely at both the right and left sides, which means there’s no clipping. None of the data in this shot is exceeding the dynamic range of the camera image capturing ability.

So, before we go on and look at some other examples and their histograms, let’s talk about metering modes, how I metered this shot, and why. Most of the time you will probably be perfectly fine to use your camera’s Evaluative Metering mode. This is where the camera takes meter readings from the whole frame, and uses a multitude of algorithms to guess what you are after, and from what I hear, does a pretty good job of setting your exposure. I say from what I hear, because I’ve only heard that this metering mode is getting quite reliable these days. I personally got used to using Centre Weighted average metering some years ago, and never switched back. Note too that I’m using the Canon definition of Centre Weighted, which is where the camera metres the entire scene but gives priority to the values metered from the centre of the frame. Please don’t confuse this with Partial Metering, which is where the centre 8% of the scene is metered, or Spot metering, where just the centre 3.5% of the scene is metered. And if you’re a Nikon user, I believe Nikon uses the term Centre Weighted to refer to what Canon calls Partial Metering, so if I’m not covering your own camera’s terminology, please check your manual for information on the various metering modes available.

I find though that centre weighted just fits my shooting style. I probably use it for 98% of my shooting. It gives me a less computed, straight reading of the light in scene, so I know from experience when I’m going to need to use exposure compensation and when I’ll be OK. I may well be able to get away without using exposure compensation as much as I do if I was to give Evaluative Metering a try, but I just don’t seem to be able to kick the habit of using Centre Weighted. By all means though, if you are used to using and are happy with Evaluative Metering, continue to use it. I’m not suggesting you change your own shooting style.

The other metering mode I use is spot metering. Not all cameras have this, and before buying the Canon EOS 5D which does have it, I used the Partial Metering, which as I mentioned earlier meters the centre 8% of the frame, as opposed to the centre 3.5% for Spot Metering. Again, this can vary by camera, so please check your camera’s manual if you want accurate figures. Anyway, as I know that the pink blossom in the scene we have just looked at are quite light in colour, and likely to require around plus one stop of exposure compensation, I can just use spot metering, because the target is very small, and meter of one of the flowers. In this shot I chose to spot meter from the flower just left and slightly above centre, which is also the flower I focussed on. This is probably the first actual straight answer to part of John’s question. I meter from the highlight, and when appropriate, the same part of the scene that I am going to be focusing on; the main subject. I will then use that as a base for any exposure compensation that I know will be necessary. If you’d rather not use Manual Mode, what you can do is set your camera to say plus one stop of exposure compensation because we know the flower is quite a light colour, and then once you’ve spot metered from it, push your exposure lock button. This will hold that exposure for a number of seconds while you recompose the shot. This is of course not necessary if you’re metering from something in the centre of the frame, because you won’t be recomposing.

If your scene includes something large areas of something very bright or very dark, I would remain in centre weighted metering mode. I only use spot metering for getting a reading from a small object in the scene. Let’s take a look at another example, image number 1203, in which we can see a shot of a Red-Crowned Crane from my December 2006 trip to Hokkaido. Note how the bird and snow in the background take up most of the shot, yet it is not under exposed. When I’m shooting these white birds, or anything that I want to shoot that may move from a light background, as in the snow in this shot, to a dark background, such as the dark trees that form a back drop at this particular location, I usually switch to manual mode as I mentioned earlier, and take a reading from something that I know is the same colour as the subject, in preparation for something actually happening, like this bird coming close to me and doing a bit of preening. In the case of these cranes, they are the same colour and reflectance as the snow, so the first thing I do when I turn up to shoot these cranes is set my camera to Manual Mode, and point it down at the snow, filling the frame with it, and having set my aperture for the required depth-of-field, I adjust the shutter speed while looking through the finder, keeping my eye on the exposure indicator. That caret that moves up and down the scale that tell you how much higher or lower than zero your exposure is. Remember that the camera is trying to make everything 18% grey, and doesn’t know that I’m pointing my camera at a totally white scene, so I have to use my own calculator, that storage device between my ears to recall how much I have to exposure compensate for snow, and that is around 1 and 2/3s of a stop on a relatively bright day. So once the caret is pointing to one and two thirds above zero while pointing my camera at a totally white scene, I know I’m set to go. I will again shoot a few test shots and check the histogram before things start to heat up. Once you’re set up, no matter what colour the background is, I know I’m going to have perfectly exposed cranes and snow. If the light changes, I will of course have to change my exposure, so I tend to keep an eye out for light changes and repeat this exercise throughout the day, especially in the first and last few hours of the day when light changes pretty quickly. Note that if there was no snow, but I still wanted to avoid exposure mistakes, I’d probably switch to spot metering here again and just meter off of one of the birds, even if they were some distance away.

So let’s now take a look at the histogram for this shot as well. This time you’ll see a large spike over on the right side, but not touching the right shoulder. This represents all white in the shot. There are various shades of grey in the background made by the texture in the snow, which we can see by a very small band of information across the bottom centre of the histogram to the left, and then at the left, there’s a couple of small spikes again. These are of course the dark grey and blacks of the bird’s neck and tail feathers. You can see that I’m perhaps even touching the left side there, but there isn’t a spike, this means that some parts of this black are perhaps clipping, but I’m not going to worry about that, as I would much sooner see nice pure whites, than any more detail than this in the black tail feathers. Note too before we move on that the photo here is exactly as it was captured. This is the RAW file. The only thing that you’ll notice is that I have left the Lightroom default of adding +50 to the brightness. I’m not sure right now why that is the default, and I actually removed it for a while when I first started using Lightroom, but decided most shots looked fine with it, and left it that way. I do though reduce or remove this totally if this causes a shot to start clipping when I don’t want it too.

Let’s start to look at some examples though where I really would concentrate on the main subject, even at the expense of the dark areas, and sometimes even playing off of those dark areas for effect. In image 1360, shot last Friday morning, which for the sake of those catching up on the archives later was the 30th of March, 2007. Here you’ll see again, some cherry blossom flowers, this time though against a very dark background. I’m not going to go into much detail about the shot as I might well do a Podcast on these images in the near future, but what I need to say is that I was shooting these flowers shortly after it stopped raining for two reasons. One not relevant is because I wanted to capture the blossom with the droplets still on them. The second and more relevant reason is because when it rains, cherry blossom trees’ bark become very dark in colour, and this enables me to get the very effect I was aiming for, which we can see here. There is so much contrast between the bright blossom and the trunk that I have no way of capturing both with my camera’s sensors dynamic range. Now I know someone is already thinking of mailing about using HDR or High Dynamic Range technology to overcome this, but please don’t miss the point. I want these dark areas. This was what I visualized.

Let’s take a look at the histogram for this image as well. We can see now that I have a small, pretty broad hump along the right side of the histogram, stopping just short of the right shoulder. This is of course the cherry blossom itself. Then there is almost no information for most of the left half of the histogram, until the last 10% or so, where we see a large spike, going right the way to the left side. So as we see in the shot, this is representing total black in some parts of the wet bark that contain absolutely no detail what so ever. I chose to go this way to not only allow me to capture the flower faithfully, but to also increase contrast between the main subject and the background.

Here again, I’m metering for the highlights. So far that’s three out of three. Let’s look finally at an example of where I have metered for the darkest part of the shot, allowing other areas to be totally over exposed and blown out. In shot number 1369 we can see a cherry blossom tree shot from below with a wide angle lens. In fact, I’m not going to talk about this lens today, but it was shot with the new Canon EF 16-35mm F2.8L II USM lens. All I’ll say for now is that after shooting a few shots today, including the one we’re looking at right now, Canon have made a very good job of redesigning this lens. Anyway, in this shot we can see that I have exposed for the small batch of blossom near the bottom of the tree trunk, allowing the overcast sky visible through the canopy of the tree to be totally over exposed. Let’s again look at the histogram for this shot, and we’ll see that this time because the tree trunk was not wet, even with exposing for the flowers the tree trunk is not lost in the shadows. We can see this by looking at the small peaks to the left of the histogram. They are touching the left shoulder, but not spiking up it at all. There’s then a steady slope going from the left third, getting higher towards the right, which is all the pink blossom across the frame, then a nice big fat spike on the right shoulder. This is the overcast sky, totally blown out at the top of the shot. This was of course intentional. It was an overcast day, so the sky had nothing to add to the shot, so I used it’s brightness to add a beautiful surreal effect to the flowers in the canopy. I was again in Manual mode, but could have used any of the technique mentioned today to meter for this. I’m really just showing you this for an example of when I will not expose for the highlights. I must admit though, it is not that often that I do this. I used this image today, as I shot it only this morning, and it fit the bill. Also I didn’t want to go searching through my gallery for another example.

So, we’ll start to wind up a little here, but basically if you are not really sure what part of your shot you should meter from, but are not sure either that it’s going to be a straight forward “trust my camera’s meter” exposure, switching to spot meter mode or partial metering if you don’t have spot metering, and just take a reading from the various parts of the shot that you are concerned about. Although you can do in Aperture Priority or Shutter Priority by noting how the shutter speed or aperture settings change, it’s far easier to switch to Manual Mode and just watch that little caret move up and down the exposure indicator in the viewfinder. You might find that some areas of the shot are actually a little brighter or darker than others, and this will start to guide you in your decision as to what to meter for. If you don’t have much time to play around, or still don’t know what to meter from, try to find something mid-toned in your scene. If you are outside a good thing is grey rocks, or concrete pavement or sidewalk. And as long as you’re shooting digital and have a histogram to look at, you can always just take a test shot and check it and adjust your exposure accordingly.

Also, if you can select an RGB histogram in the custom settings of your camera, I suggest you use it. It will really help to spot if just one of the colours is blowing out, because this is not always noticeable in the standard brightness histogram. Red for example might be hitting the right shoulder in a photograph of a field of poppies in bright sunlight, but when viewing a normal averaged out light histogram, this will not always show up. If you use an RGB histogram, you’d be able to see Red clipping very easily, and reduce your exposure accordingly.

So, in summary, I basically expose for the highlights pretty much most of the time. This is because the highlights in a digital photo are the first place that I feel really stand out when exposure is a little off, far more than totally black shadows. This is not a hard rule though. As in the last example I looked at, you might want to let the highlights blow out sometimes as well. One thing to watch with blown out highlights that we shouldn’t finish without mentioning is that they bleed. If you have an area of overexposure the light tends to spill over into neighbouring pixels and you will lose detail in darker areas close by too. This may be the effect you’re after, but keep it in mind as it might not always work for you.

Also, I mentioned HDR or High Dynamic Range images earlier. This is something that I’ve not really gotten into very much, although I would like to. Basically you shoot multiple exposures of the same scene and then use Photoshop or another tool to blend the shots together and create a single image with a very wide dynamic range, much wider than any of the current cameras on the market can create. This is an option, and it might be for you, so worth bearing in mind. Also, I have mentioned in previous episodes about using gradual neutral density filters or blending multiple images in Photoshop to get around the dynamic range limitations of our cameras, but I’m not going to go over that again today.

Finally, you’ll have noticed that I called this episode “Metering for ‘Optimum’ Exposure” not correct exposure. In the past, I used the term correct exposure and was promptly taken to task on this, and rightly so. As the photographer, we decide how we want to portray the world captured in our images. We might decide to use high-key or low-key techniques, in which certain areas may be well over or under exposed, but if that is what we are aiming for as artists, then it becomes correct. By saying optimum though, I’m giving us the leeway to make the exposure exactly how we want it to be, not some predetermined ‘correct’ exposure, if there could even be such a thing.

So that’s it for today. Thanks very much to John Grant for the great question. I hope I’ve answered it sufficiently. If anything remains unclear, please do drop me a line and I’ll try to provide more information. Remember that if there’s anything that any of you have questions about, please do drop me a line or record an audio message using the MobaTalk applet on the top page at martinbaileyphotography.com. If it’s something that I already understand and have experience with, I should be able to get around to doing an episode on it at some point.

Anyway, with that I’d just like to say thanks for listening, and have a great week doing whatever you do. Bye-bye.

Show Notes

Music from Music Alley: www.musicalley.com/

Subscribe in iTunes for Enhanced Podcasts delivered automatically to your computer.

Download this Podcast in MP3 format (Audio Only).

Download this Podcast in Enhanced Podcast M4A format. This requires Apple iTunes or Quicktime to view/listen.

0 Comments