Visit Library for MBP Pro eBooks |

Over the last week, I’ve been on safari. Not in Africa, or even a cheesy safari park, but in three drops of water on a microscope slide. I spent multiple hours looking at a number of slides with drops of river water on them from the Tama River, which runs just five minutes from our Tokyo apartment. The experience was, to a degree, relatively life-changing. I was amazed by not only the number and variety of organisms found in just a few drops but possibly more intriguing was their resilience.

Not only did they seem to be perfectly happy to live in a glass jar for around four days before I put them back in the river, but they also seemed to be mostly fine with being tapped off their root or scraped off of a piece of reed, and sandwiched between two pieces of glass for hours at a time. They just kept going about their business, rummaging around, eating, and crapping, regardless of where they were.

I actually emptied the four jars of water and various organisms back into the river last Sunday, and I’ve spent most of the last week creating a video, which I’ve embedded into this blog post below. I’d have completed this a day sooner, but DaVinci Resolve decided it would be a good idea to delete four days worth of editing while I had breakfast on Thursday, and the rest of Thursday was taken rebuilding what I’d lost, so this has taken longer than necessary, but I’m happy with the results. The video is the main content for this week, but I did want to share a few photos with you as well, and talk about some of the creatures that I met on my microscope slide.

I’d also like to warn you before you look at the video, that it may actually disturb some people to know what is in plain old river water. I found the majority of the organisms attached some plant life that was put into my sample jars, and the majority of what I saw was, in my opinion, as cute as can be. But while looking at some cute plankton, we were occasionally visited by what looked like, in comparison, I giant almost transparent anaconda snake, with lots of little four-toed legs.

I’ve put two warnings in the video, shortly before the anaconda enters the screen, and I mention how long it will be there as well if you want to overt your eyes. I personally found it fascinating, like the rest of the organisms, but I imagine some people will not be overall happy with the visit. In fact, even the plankton going about its business might disturb some people, so only watch if this sort of thing interests you. Anyway, here is the video, starting with an explanation of the project and a bit of footage of fetching the samples, followed by around 30 minutes of footage through the microscope. As you watch, keep in mind that there are two main types of plankton. Phytoplankton, which are plants, and zooplankton, which are animals. Pretty much everything in this video falls into these two groups of plankton.

I hope you enjoyed the video. Let’s also take a look at a few of my favorite photos from the project, and I’ll explain some of the challenges faced as well. First up, here is a light field photograph of a Nematode otherwise known as a roundworm. These are very common, and can exist in both water and in soil, and are also able to live in acidic substances such as vinegar. They can be parasitic, and some species will bore into the soles of human feet if you walk barefoot in a river or on soil with Nematodes in it. I’m including this shot mostly to start explaining the difficulties of photographing plankton.

Because this was light field, with light being passed directly through the microscope slide, there was quite a lot of light to work with, especially as I’ve customized my microscope to add more light via an additional LED ring light around the original single LED light, but still, to try and freeze this Nematode, which tend to wriggle around all the time, I increased my shutter speed to a 1/500 of a second. With this shutter speed, because of the higher light levels, I was able to use an ISO of 6400, which is good compared to most of the following examples I’ll share.

I then switched to dark field microscopy, which, as I explain at the start of the video, is a technique that can be used by placing an opaque disk between the light source ant the subject, and adjusting the size of the disk, the distance of the light from the slide, and the diaphragm that controls the diameter of the light, so that the light spills onto the subject from the sides rather than passing directly through it, as in the previous image.

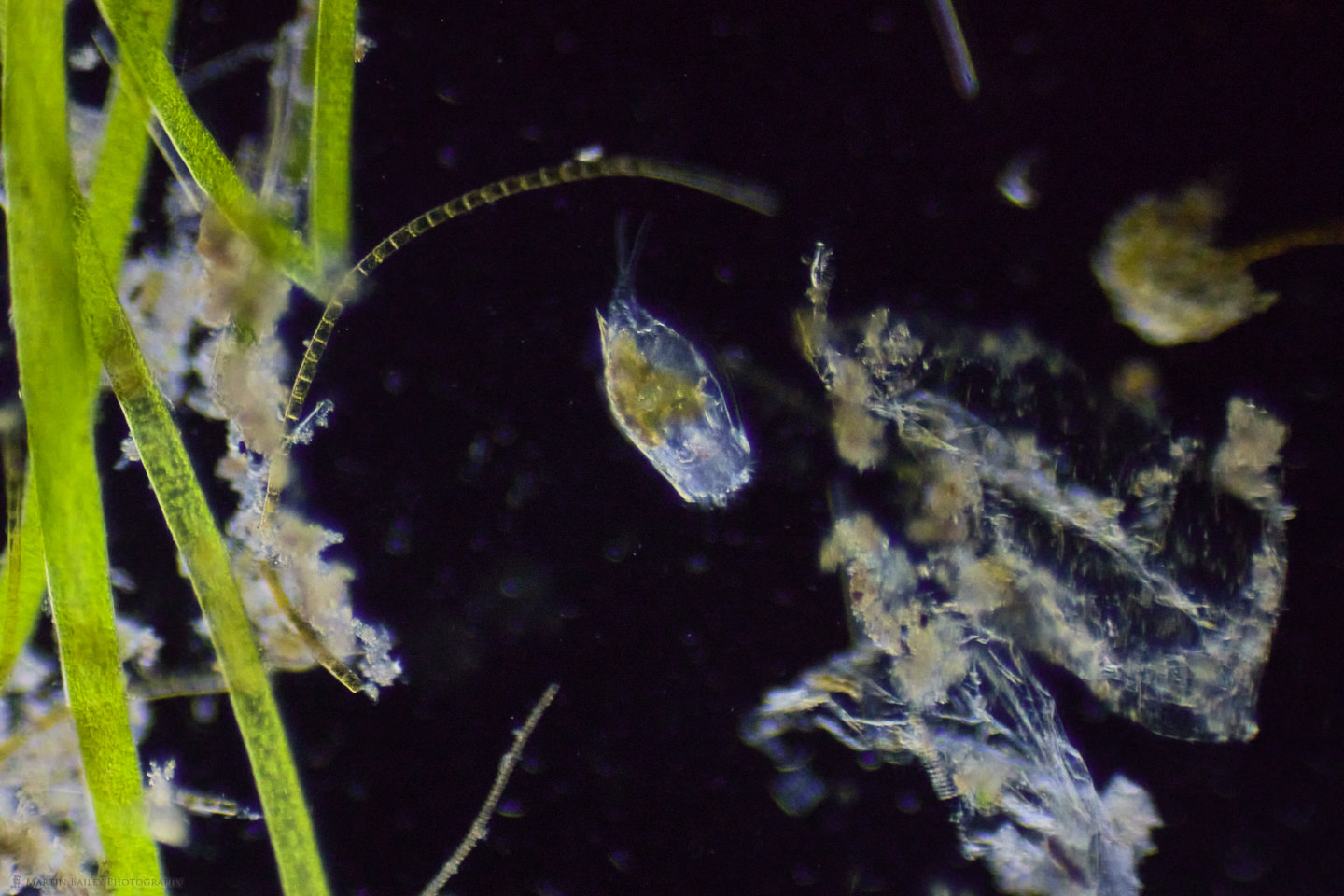

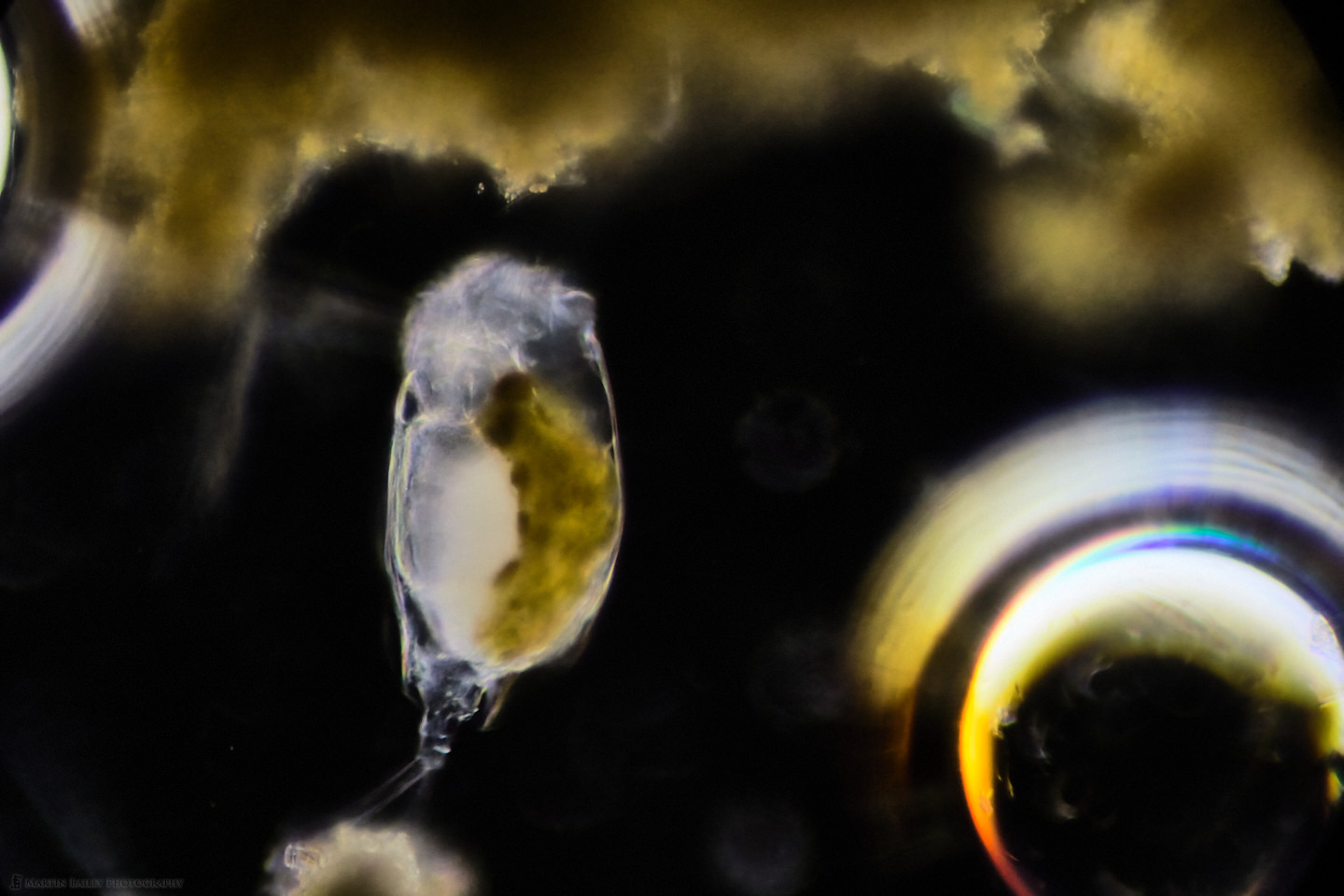

What you are looking at here is a Lapadella, a type of Rotifer, which in my Japanese Plankton book translates as a Rabbit Rotifer, probably because the two-toed tail that you can just about see in this image looks like rabbit ears. You’ll see that better in the following images, but I wanted to include this to show how dark field microscopy illuminates the surrounding phytoplankton, and in my opinion makes for much more pleasing images. There is also less to clean up. With the previous light field image I had to clean up the background quite a lot, but this image is pretty much straight out of the camera, with just a simple tone curve applied to increase the contrast a little. Also, to try and freeze this Rotifer as it swam around, I tried working with 1/1000 of a second shutter speeds, which required ISO 20000 to get this exposure, so I was starting to push the limits a little here.

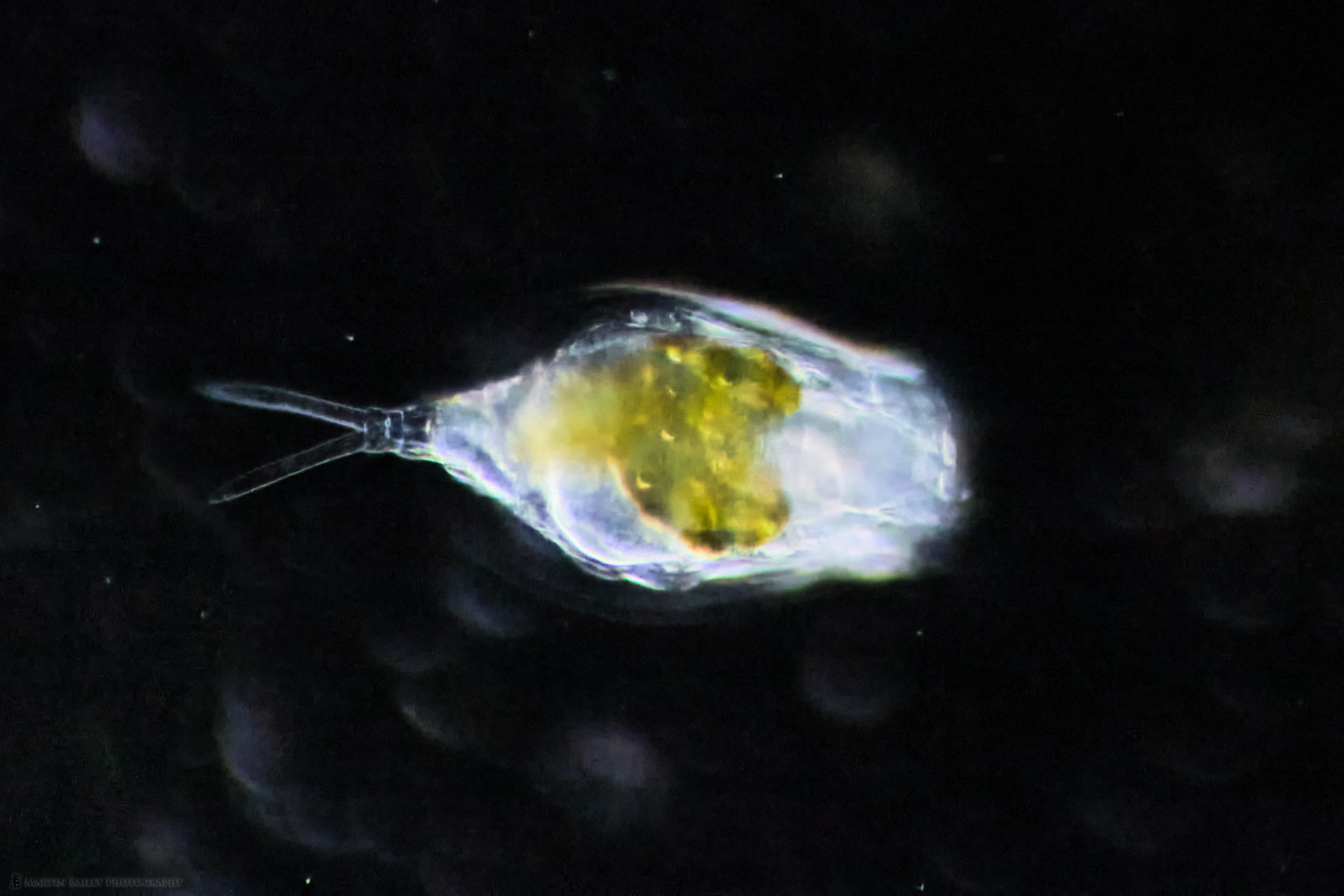

For this next image though, I changed to the 40X objective lens, to get a closer look at the Rabbit Rotifer, but with that, because of the lower light that the lens collects at this magnification, the ISO jumped up to 51200 at 1/1000 so I had to run this through On1’s NoNoise AI software to clean it up. That still produces a usable image, but definition drops slightly using these settings.

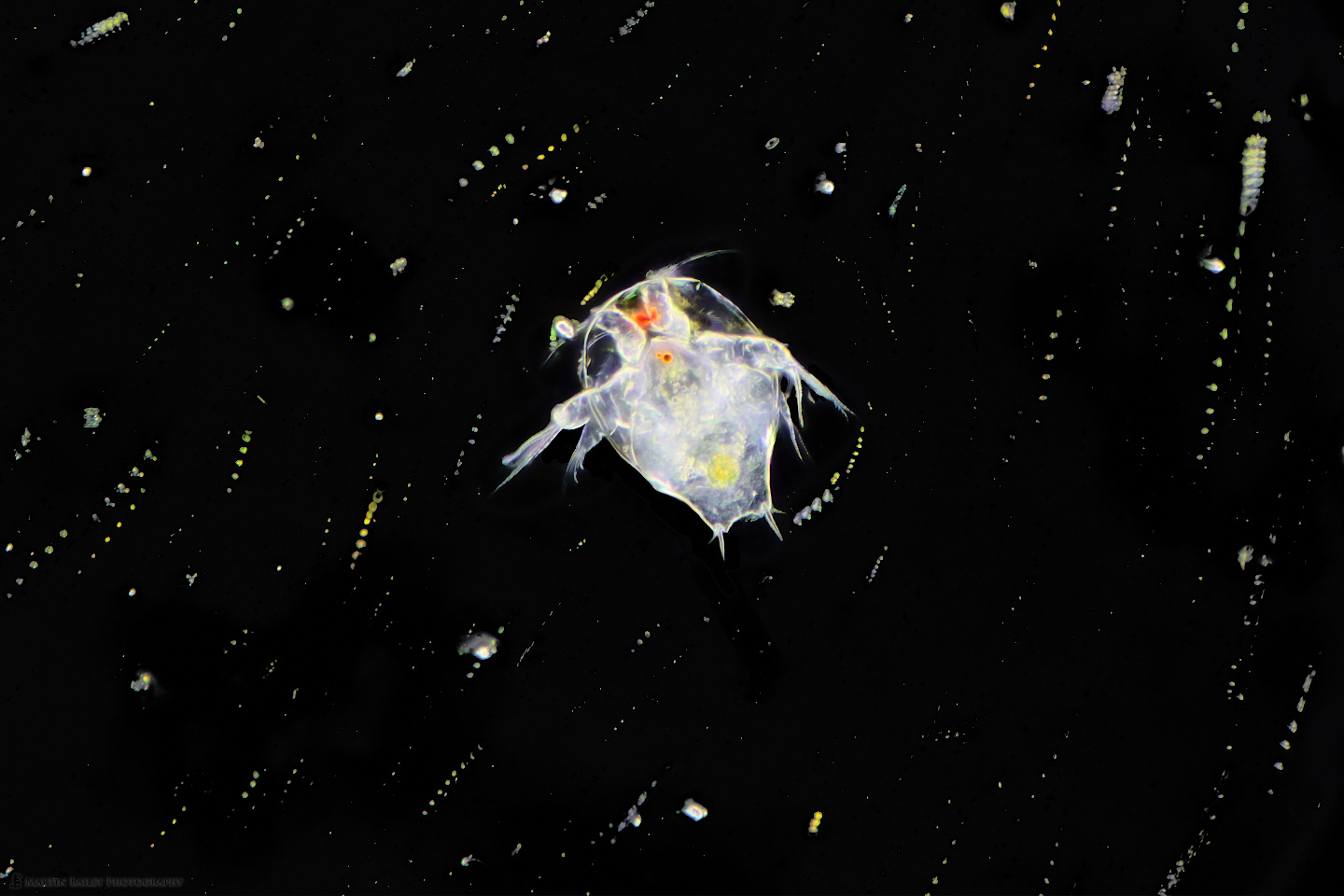

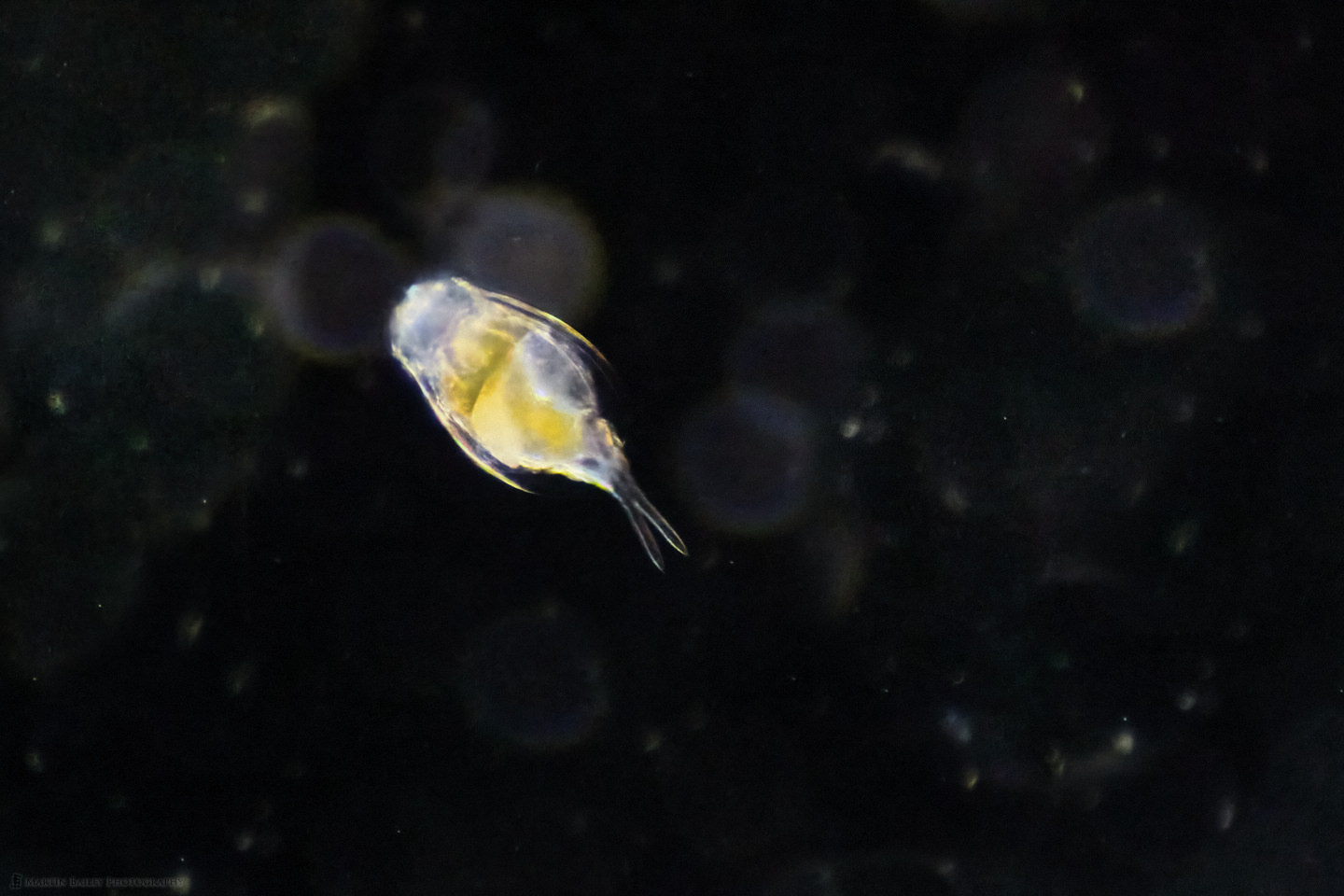

I’m also fighting with the poor image quality that I get with my camera adapter, as well as the very shallow depth of field. I have been overcoming these restrictions by doing a lot of focus stacking, but for moving subjects, focus stacking isn’t possible. I got lucky with this next photo, as this creature, which I believe is a type of Copepod, stayed very still for a while as I shot a 39 frame stack. Shortly after I finished my stack he swam away at speed, so I was very lucky, but the stack also recorded trails in the debris that flowed past the organism as I made more frames, which I thought was quite effective as a photograph as well.

Because it was stationary though, I was also able to reduce my shutter speed to 0.3 seconds and use ISO 400, so the image quality is greatly increased with this settings and the focus stack. This was one of just a few images that I was able to shoot like this though, with the majority of the rest being single shots, struggling with shutter speed and ISO settings trying to make the most of what I was being presented with.

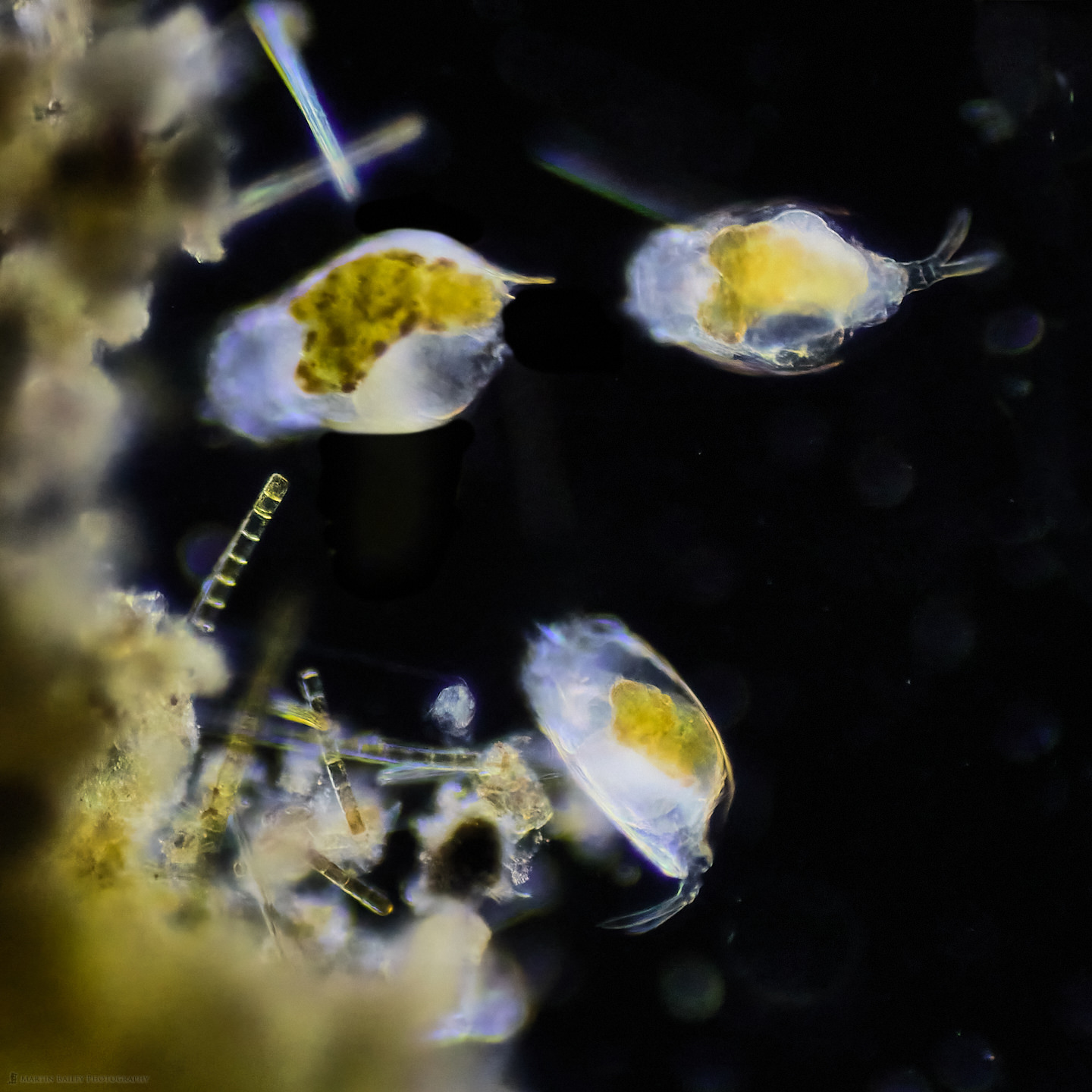

Having learned from the first few days that I really needed to get my ISO down lower than it was going, I reduced my shutter speed to 1/250 of a second, and accepted a little more subjected movement over grain for this next image, in which I was able to get three Rabbit Rotifers in the frame together.

They are providing a top, bottom and side view, so this is one of my favorite shots that really illustrates this beautiful life from.

In the next image we can see the outlined lorica which almost look like little wings, but it’s actually just the outer shell of the Rotifer being caught by the light and actually continues down to the base of the foot.

Still at 1/250 of a second shutter speed, my ISO was a 20000 for this shot, Once again here I ran this through On1 NoNoise AI to bring the grain caused by the large dark portion of this image under control.

This final shot is another of my favorites, shot with the 40X objective, the Rabbit Rotifer was stopping still for a few moments at a time, so I reduced my shutter speed to 1/125 of a second, and got a few shots where it was still, and relatively clear. There are also a couple of air bubbles which I was intrigued to find that the plankton has a very hard time with. The surface tension of the air is impenetrable despite seeing the Rotifer interact with the air a few times. It’s like a solid wall to them.

I don’t really have anything that I’m all that happy with of the Mouse Rotifer, which appears frequently in the video. They are slightly smaller than the Rabbit Rotifer, but their behavior is just like little mice, scurrying around in their environment, eating the algae on the phytoplankton. Anyway, we’ll leave it there for now. Please do watch the video when you have time. If you are listening to this you can jump directly to the video on Vimeo with the short link https://mbp.ac/universe.

Show Notes

Check out the video on Vimeo here: https://mbp.ac/universe

Subscribe in iTunes to get Podcasts delivered automatically to your computer.

Download this Podcast as an MP3 with Chapters.

Visit this page for help on how to view the images in MP3 files.

0 Comments