Following on from our Why Expose to the Right (ETTR) episode a few months ago, I received a question from listener Christopher Pearson, asking how I meter in Manual mode, so today, I’m going to explain my techniques for metering in manual mode.

First of all, I want to explain that I leave my camera in the Evaluative Metering mode now. For long time listeners, you may remember that long ago I used to use center-weighted average metering, but I stopped that years ago, because I now just like to see what the camera “thinks” about a scene, and Evaluative metering allows the camera to think for itself a little more. I know people that use spot metering as well, which works well, but I haven’t used spot metering in years either, as I just don’t feel there’s a need for it.

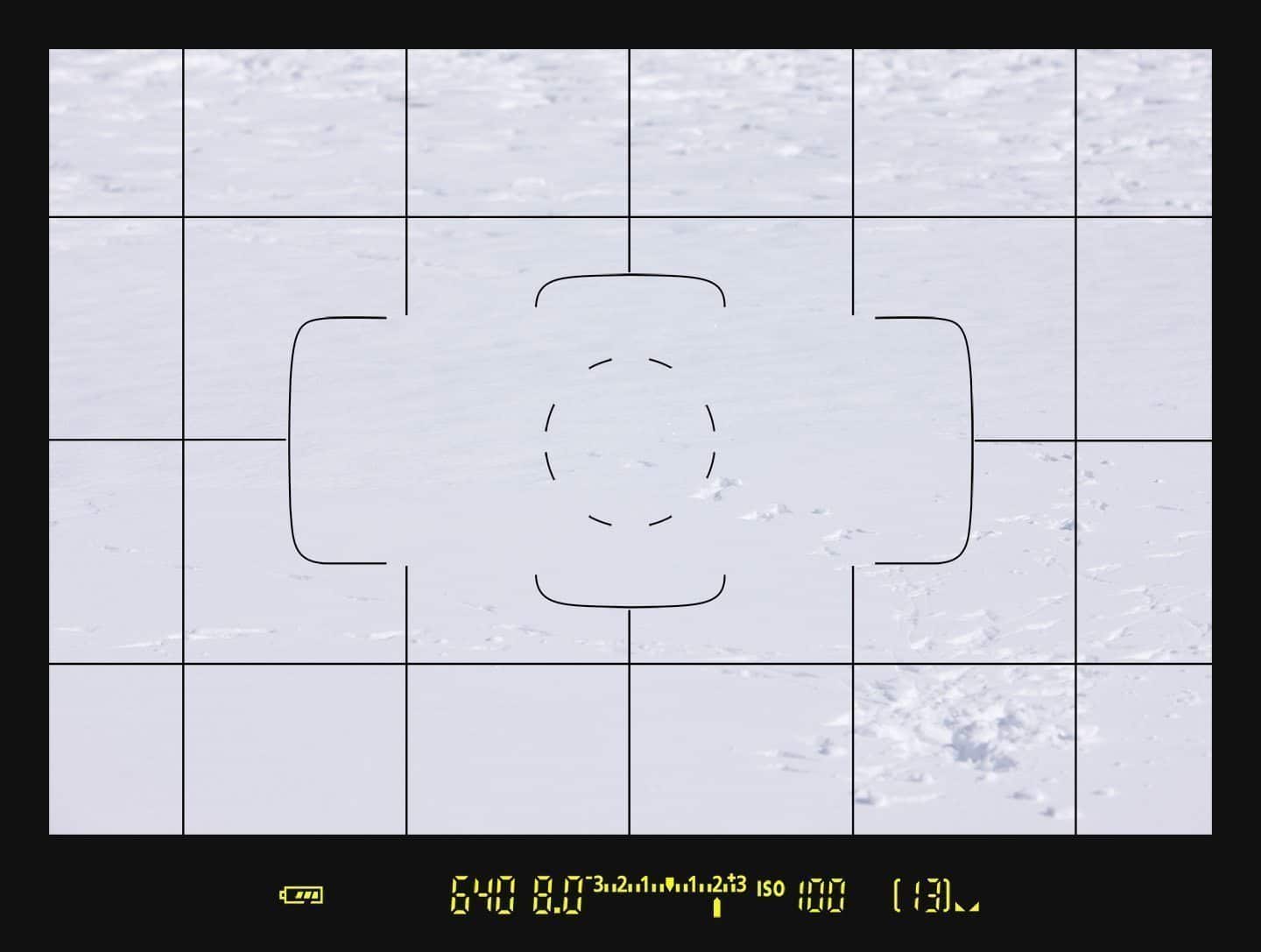

I should also explain that just because the camera is set to Manual mode, that doesn’t mean that the camera stops metering. As you look through the viewfinder in Manual mode, the little caret that indicates where the camera think the exposure is, still works, so for example if I have my camera set for too short an exposure compared to how the camera sees the scene, the caret will be below zero on the Exposure Level Indicator scale, and if I have my exposure set too high, the caret will be above zero.

This means that when shooting in Manual mode, we aren’t flying blind. We still have the benefit of seeing where the camera thinks we should be, and that allows us to quickly make adjustments based on what we see in the scene. I’ve spoken about this before, but just to recap with an example, but the most common manual mode compensation that I do, is when photographing in the snow.

Metering for a Snow Scene

The first thing I do when I am shooting a snow scene, is point the camera down slightly, and fill the frame with snow, as you can see in this example image (below). I usually start at ISO 100, and then set my aperture for the depth-of-field that I want to shoot at, and then start to adjust my shutter speed, until the meter indicator shows me that I am 2 stops over zero.

I aim for plus two stops, because I know that is how I need to exposure for whites to be white, and not grey. Remember, the camera wants to make everything 18% grey, so without this manual compensation, the photo would look more like this example (below) and we don’t want that.

Once I have my exposure locked down like this in Manual mode, I know that my snow is going to be beautiful and white, and the red-crowned cranes that I shoot are also going to be perfectly exposed, even with texture visible in their beautiful black feathers. If I left this up to the camera, the white of the cranes would be grey, not white, and their black feathers would be so dark there’d be no texture in those areas at all.

Also, in case you are wondering why I wouldn’t just use plus two stops of Exposure Compensation in Aperture Priority mode, that’s because the birds can move from their white snow background, to a very dark background in an instant, as we see in this next photo (below). And when that happens, instead of the camera underexposing the whites, trying to make them grey, it sees all that dark and increases the exposure trying to make the black grey, and the white bird goes super-nova.

So remember, for snow scenes, if you fill the frame with snow, and adjust your exposure so that the camera thinks you are two stops over exposed, you will be in good shape. For very dark scenes, you would usually do the opposite, but as I explained in the Why Expose to the Right episode, you may not always want to do that, but if you missed that episode, I suggest you go back and check that out instead of me covering that again today.

What About Other Scenes?

With other scenes, I really don’t meter the subject as such. I literally look through the viewfinder, estimate how much of the frame is bright and how much is dark, and adjust the exposure to what I think will be close, then take a test shot and check the histogram. The estimation process takes a bit of getting used to, but the more you do it, the easier it gets. I’m usually either spot on, or just 1/3 or 2/3 of a stop under or over at tops.

I leave my metering mode in evaluative. I don’t use spot metering, because even with spot metering the camera still wants to make everything 18% grey, so I find that it takes longer to find my ideal exposure than adjusting based on a guestimate, and then shooting the test shot. I would still want to shoot a test shot even when using spot metering, and still may have to fine tune, so I just leave my camera in Evaluative Metering mode now, as I mentioned earlier.

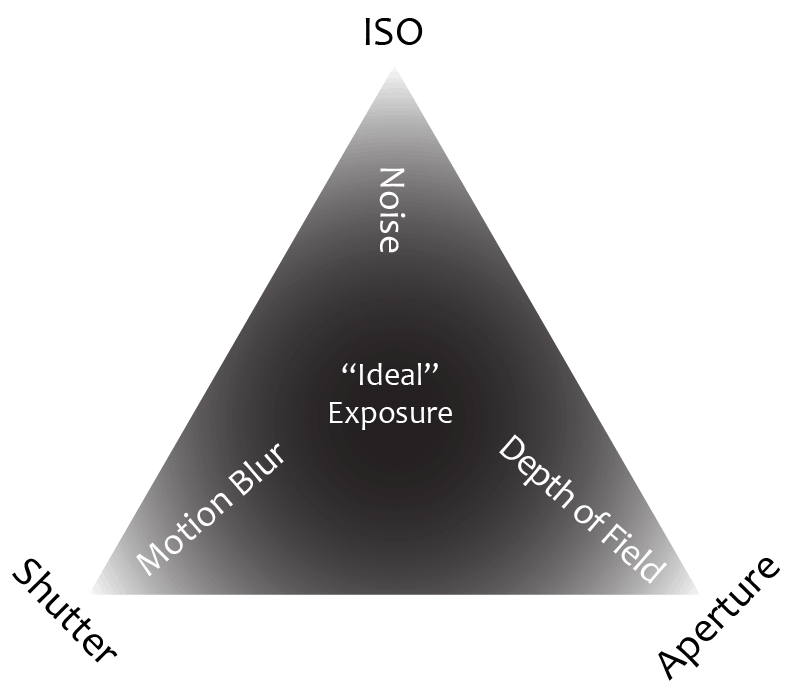

Which Parameters to Change?

To arrive at my ideal exposure, with the data almost or just touching the right side of the histogram, I might change any of the three parameters in the exposure triangle. I generally start with the Aperture because I usually want to control depth-of-field first, then I set a low ISO of say 100 if there is plenty of light, and then adjust my exposure with the shutter speed. If it turns out that my initial ISO setting was a little too low, I might revisit that and increase it some more so that I can get a shutter speed that suits my subject matter.

In the earlier example I used a shutter speed of 1/640 of a second, but for flying birds I actually like to go a little faster, so I might go to ISO 200 for a 1/1250 of a second shutter speed. Also, if there is a bit of patchy cloud around, I might find that I have to adjust the exposure every so often, and I usually do this with the ISO, so I might increase from ISO 200 to 400 while the cloud is there, then back to 200 when the sun comes out again.

How you handle this will depend on your camera. Canon cameras generally have an ISO button to select the setting you are going to change, then you just turn a dial to change it. Some Nikon cameras bury the ISO setting a little further into the menus, which can make this a bit of a pain, so you’d need to figure out the best way to make these changes for your own equipment.

No Need to be a Manual Snob

I also want to note that I’ve become so used to shooting in manual, that I have a hard time going back to Aperture Priority mode, because it actually takes me more time to adjust my exposure with exposure compensation than it does to adjust my manual settings.

I do wish however, that I was better with Aperture Priority, as it makes more sense in some situations. When I’m doing street photography for example, I am now using Aperture Priority with Auto ISO, and I’m getting used to it, but it’s hard for me.

I forced myself to use Aperture Priority for example in Namibia earlier this year, when we visited the Himba people. We were shooting in a variety of lighting conditions, and it just made more sense. For this photo of a young Himba man sitting in the doorway of his hut, my ISO was set to 400, for a 1/60 of a second exposure, with an aperture of f/3.5.

The camera would have chosen the shutter speed of a 1/60 of a second because I was shooting at 64mm with my 24-70mm lens, so it’s trying to use my focal length as my shutter speed to avoid camera shake. I’d of course set the aperture, because I was in Aperture Priority, and the camera selected ISO 400 because that’s what I needed to maintain the minimum shutter speed. I also see from the EXIF data for this shot that I had dialed in – 2/3 of a stop in Exposure Compensation, because the subject is predominantly dark. Had I not dialed in that compensation, the young man would have been too bright, probably over-exposing the highlights on his forehead, and his two sticks would also have been over-exposed.

Use a Handheld Light Meter

One last tip that I want to relay, because I found it very useful, is that if you have or can borrow one, a light meter can really help to understand exposure. Mine is a quite old Minolta light meter that is now discontinued. I think if I was to go out and buy one now, I’d go for the Sekonic L-478DR light meter, because that’s the one Zack Arias swears by.

Of course, you don’t really need a light meter now that we have the histogram on the camera, but I do still use mine sometimes in the studio. Especially when I’m setting lights up at a customers home or office. I can plug my Profoto Air Remote right into my meter, and then trigger the lights with the meter to get my readings. That’s going off topic though. The point I wanted to make here is that when I first got a meter, I was already shooting digital, but just spent a lot of time taking incident light readings, which is where you use the little white dome to read the level of light falling on your scene, and just seeing if that was close to my estimates.

Even without a camera, I would carry the meter around with me and just meter stuff. I also used the spot meter which is where you look through the little viewfinder in the meter to take a reflective reading of the light bouncing off of your subject. It can really help you to hone your exposure estimations just doing this, and also when you are out shooting. Compare how your camera sees the scene with it’s limited artificial intelligence based on stored scenes, and compare that to the raw readings from your hand-held meter. I don’t suggest you buy a meter for this, as you’ll probably never use it, but if you know someone that has one, ask if you can borrow it for a month and meter the hell out of your world for a while. It’s a lot of fun.

Anyway, that’s about it. I wish I could talk more about metering, but really, the histogram is king to me, so I generally start with my guestimate, adjust while viewing the in camera meter, and then take a test shot and check the histogram to ensure that the lightest part of my scene is just up to the right shoulder of the histogram. That’s pretty much it in a nutshell.

Show Notes

The Sekonic L-478DR light meter on B&H Photo.

Music by UniqueTracks

Subscribe in iTunes for Enhanced Podcasts delivered automatically to your computer.

Download this Podcast in MP3 format (Audio Only).

Download this Podcast in Enhanced Podcast M4A format. This requires Apple iTunes or Quicktime to view/listen.

thanks Martin for a great episode. I now better understand why and when I should use the exposure button and when to use the compensation button.

That’s great. Thanks for stopping by Shelle!

Martin, the shutterspeed in the two images of the viewfinder are reversed. At two stops +, you have to get an shutterspeed of 160. Not 640.

Greetings Marc

Of course. Thanks Marc! I’ll fix that. Except the 640 is accurate. I need to make the 2 stops faster shutter speed 2500. Doh! 🙂

I’m an enthusiast natue and wildlife photographer using manual mode most of the time.

For wildlife shots; I overexpose dark subjects and underexpose bright subjects. The metering is always in Evaluative mode. However, when the subject is located in a low light area; I use Spot metering and crank up the ISO if necessary using wide apertures.

May I have your comments on the above.

Thanks in advance.

If you are doing exposure compensation manually, you need to do the opposite of what you say. The camera usually over-exposes dark subjects, so you would under-expose them, and visa versa.

Personally, I just expose to the right for everything. If the subject/scene is very dark, I might pull it back in Lightroom later, but I still expose to the right at the time of shooting to create the highest possible quality base image. If you didn’t see my other post on this, take a look here: https://martinbaileyphotography.com/2013/07/29/why-expose-to-the-right-podcast-381/

I depend more on the histogram and highlight warnings, so rarely use spot metering, but I too also increase the ISO when necessary. It’s better to use a higher ISO when shooting rather than brightening in post later.

Cheers,

Martin.

Right now it looks like Drupal is the preferred blogging platform out there right now.

(from what I’ve read) Is that what you’re using on your blog?

my webpage … Hotels in Letterkenny